Karla Marie-Rose Derus, “Taking Notes on How Bibliophiles Flirt” (Modern Love), New York Times, February 24, 2019, pl. ST6.

During six years of singlehood in my 20s, I became a person I did not know. Before, I had always been a reader. I walked to the library several times a week as a child and stayed up late into the night reading under my blankets with a flashlight. I checked out so many books and returned them so quickly the librarian once snapped, “Don’t take home so many books if you’re not going to read them all.” “But I did read them all,” I said, unloading them into her arms. I was an English major in college and went on t get a master’s in literature. But shortly after the spiral-bound thesis took its place on my shelf next to the degree, I stopped reading. It happened gradually, the way one heals or dies.

…

On our seventh date, David and I visited the Central Library downtown.,

“I have a game,” he said, pulling two pens and pads of sticky notes out of his bag. “Let’s find books we’ve read and leave reviews in them for he next person.”

We wandered through the aisles for over an hour. In the end, we say on the floor among the poetry, and I read him some of Linda Pastan’s verse.

…

The Japanese language has a word for this: tsundoku. The act of acquiring books that go unread.

COMMENT

Shame on the librarian. The writer describes herself as “a 5-foot-3-inch black woman born to a Caribbean mother.” It troubles me to think that the librarian was judging her appearance, not her borrowing habits. What’s more, the librarian is deeply wrong to think that taking out unread books is somehow wrong. A library is an antidote to tshundoku. Unlike the bookstore which clutters your home shelves, you can take a chance with a library book that may not turn out to be worth reading. (See:

What to Do With all the Stuff That's Cluttering your Home;

Can't. Just. Stop).

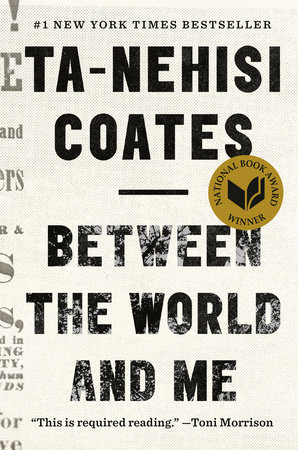

As other library stories relate, the books that people read and/or buy become deeply personal markers of who they are. Even after Karla stops reading, she considers the books she has read essential to her self perception. Her online dating profile is listed under the screen name “missbibliophile” and her taste in literature speaks for her personality. David, the boyfriend reads history and nonfiction; Karla prefers writers of color and immigrant narratives (writers on her list like Zadie Smith, Arundhati Roy and Edward P. Jones indicate the importance of diversity to her self-image) Can they overcome their differences to combine their bookshelves?

Like the writer, I experienced a period of non-reading, but I don’t think it was related to romantic disappointment or intellectual fatigue. I believe I lost my ability to concentrate due to too much screen time. I decided it was a big problem that I had stopped reading books and I cured myself by sitting down with Infinite Jest by David Foster Wallace until I had read it all the way through. A distraction-free long distance Amtrak trip was helpful to the project of becoming re-literate.

The library game the two lovers play is charming. It reminds me of students who leave paper money in their dissertation to reward anyone who bothers to read their work. Other library stories feature ephemera found in books (See:

Lee Israel) or marginalia (See:

When Puccini Came, Saw and Conquered). In academic libraries one sometimes finds texts marked up with notes or highlighting from previous readers. Sometimes this seems like annoying defacement, but it’s also an insight into what impressed another reader. I shouldn't admit it, but I don't always mind if library books are marked up if it's done in pencil and not fluorescent-yellow ink.

The library in this story is also a meaningful place. The two lovers go there on a date. When David proposes he does it by tucking a note into the pages of a book.